Guidelines for submitting articles to Hacienda Riquelme Golf Resort Today

Hello, and thank you for choosing Hacienda Riquelme Golf Resort.Today to publicise your organisation’s info or event.

Hacienda Riquelme Golf Resort Today is a website set up by Murcia Today specifically for residents of the urbanisation in Southwest Murcia, providing news and information on what’s happening in the local area, which is the largest English-speaking expat area in the Region of Murcia.

When submitting text to be included on Hacienda Riquelme Golf Resort Today, please abide by the following guidelines so we can upload your article as swiftly as possible:

Send an email to editor@spaintodayonline.com or contact@murciatoday.com

Attach the information in a Word Document or Google Doc

Include all relevant points, including:

Who is the organisation running the event?

Where is it happening?

When?

How much does it cost?

Is it necessary to book beforehand, or can people just show up on the day?

…but try not to exceed 300 words

Also attach a photo to illustrate your article, no more than 100kb

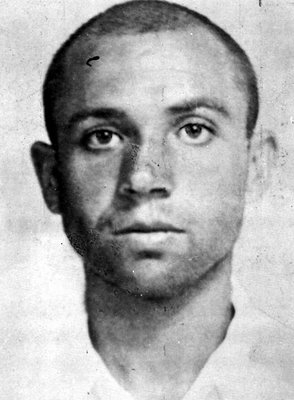

Miguel Hernández (1910-1942), poet of Orihuela

A poet of powerful simplicity, who died in the prison following the Spanish Civil War

Miguel Hernández is one of Spain’s most widely respected poets of the 20th century, and his works are studied in secondary schools throughout this part of Spain as part of a general literary education.

Miguel Hernández is one of Spain’s most widely respected poets of the 20th century, and his works are studied in secondary schools throughout this part of Spain as part of a general literary education.

He died in prison following the Spanish Civil War and is renowned for his powerful and simple poems, the most studied works written to his wife while dying in prison from tuberculosis.

Miguel Hernández Gilabert was born in Orihuela on 30th October 1910 is in Calle San Juan, in Orihuela, one of four surviving children.

Visitors to Orihuela can see the family home in which he grew up, a simple single storey property, typical of those on the outskirts of the town at this period in time, purchased by the Town hall and converted into a small museum in 1981.

The area in which the house is situated is now known as the “Rincón Hernandiano” and is close to the Colegio de Santo Domingo, one of the most important religious buildings in Orihuela but his family were humble people, his father a goatherd, so although Miguel grew up in a happy home, there was no literary tradition in his upbringing.

The area in which the house is situated is now known as the “Rincón Hernandiano” and is close to the Colegio de Santo Domingo, one of the most important religious buildings in Orihuela but his family were humble people, his father a goatherd, so although Miguel grew up in a happy home, there was no literary tradition in his upbringing.

Children growing up in areas such as this had little expectation of climbing out of the poverty into which they were born, lack of money and opportunity condemning most to following the footsteps of their parents and undertaking an agricultural career or seeking manual work in the cities.

Miguel Hernández had a very basic education from the local state school but was encouraged to develop his interest in literature by a local priest, but in spite of his poor background, began writing poetry. In 1931 he went to Madrid to try and establish a literary career, but returned to Orihuela after running out of money, however, he managed to publish his first book of poetry, Perrito en lunas ( lunar expert) in 1933, followed by a play, Quién te ha visto y quién te ve y sombra de lo que eras (He Who Has Seen You and He Who Sees You and the Shadow of What You Were) shortly afterwards in 1934

At this point he had been heavily influenced by the Generation of ’27 movement, ( a movement of influential poets who experimented with avant-garde poetry between 1923 and 1927 ) and later joined the Generation of ’36 movement, alongside Camilo José Cela and many others, mixing in literary circles after having returned to Madrid in 1934. This was a movement of artists, poets and playwrights who were producing material at the time of the Spanish Civil War, most with Republican sympathies.

At this point he had been heavily influenced by the Generation of ’27 movement, ( a movement of influential poets who experimented with avant-garde poetry between 1923 and 1927 ) and later joined the Generation of ’36 movement, alongside Camilo José Cela and many others, mixing in literary circles after having returned to Madrid in 1934. This was a movement of artists, poets and playwrights who were producing material at the time of the Spanish Civil War, most with Republican sympathies.

He began to gain recognition, and worked with Pablo Neruda on the journal, Caballo Verde para la poesía, mixing with other influential writes including Federico García Lorca, who was executed in Andalucía, the circles he moved in supportive of the Republican movement. In 1936 he produced the book “ El rayo que no cesa (Unceasing Lightning) when war broke out in Spain.

Hernández became part of the Republican movement, using his talents as a writer to produce outspoken propagandist poetry, as well as actively participating in the fighting himself. In 1937 he produced “Viento del pueblo”, followed by El Hombre acecha in 1938, before taking a break from the fighting in 1937 to return to Orihuela and marry Josefina Manrea, with whom he was to have two children. Josefina was a seamstress by trade, her father a member of the Guardia Civil, who looked after the prison in Orihuela.

Hernández became part of the Republican movement, using his talents as a writer to produce outspoken propagandist poetry, as well as actively participating in the fighting himself. In 1937 he produced “Viento del pueblo”, followed by El Hombre acecha in 1938, before taking a break from the fighting in 1937 to return to Orihuela and marry Josefina Manrea, with whom he was to have two children. Josefina was a seamstress by trade, her father a member of the Guardia Civil, who looked after the prison in Orihuela.

Their first child died aged just ten months, but the second, Miguel, survived until 1984. Sadly he was to see little of his father: Miguel senior was too outspoken in his support for workers’ rights, and when the war ended he became first a wanted man and then a prisoner when he was caught by the Guardia trying to flee to Portugal in 1939. He was in fact sentenced to death, but a few months later the sentence was commuted to a 30-year prison sentence, perhaps in order to avoid Hernández becoming a martyr to his cause like Federico García Lorca, and due to the pleas of his influential friends.

He returned to Orihuela but was re-arrested and sent back to prison where he contracted tuberculosis. Conditions in prisons after the Civil War were brutal, prisoners routinely starved, beaten, deprived of clothing and left in cold, damp cells with no heating and no medical assistance and thousands are known to have died or been executed in the reprisal killings which took place in the first years of dictatorship.

He returned to Orihuela but was re-arrested and sent back to prison where he contracted tuberculosis. Conditions in prisons after the Civil War were brutal, prisoners routinely starved, beaten, deprived of clothing and left in cold, damp cells with no heating and no medical assistance and thousands are known to have died or been executed in the reprisal killings which took place in the first years of dictatorship.

Hernández failed to recover from his tuberculosis and died in Alicante on March 28th 1942.

It was while in prison that he wrote much of his best known poetry, both romantic and political. The dual tragedies of the Civil War and inability to be with his wife and son combined to generate powerful verses, simple language making a direct point in his regular correspondence, his anger at injustice interspersed with tender and poignant longing for his family and freedom. “Nanas de la cebolla” is probably his most famous work ( see below) a poem written to his wife who complained that her and her baby son had nothing to eat but bread and onions.

There are several places which can be visited in Orihuela with links to Miguel Hernández:

There are several places which can be visited in Orihuela with links to Miguel Hernández:

• The family home next to the Colegio Santo Domingo has been acquired by the Town Hall and is now a museum commemorating both the poet and the typical way of life of the early 20th century in Orihuela.

• The Miguel Hernández University in Elche, apart from being named after the poet, also has a campus in Orihuela where various degree courses are taught.

• The Centro de Estudios Hernandianos has a dual function, firstly spreading the Word about Miguel Hernández himself, and secondly acting as a centre for literary events within the municipality of Orihuela.

• The Rincón Hernandiano is the house in which he was born and includes a display dedicated to the poet and a “ Ruta Hernandiano” is also available from the tourist office giving visitors the chance to follow a route based on the footsteps of the poet.

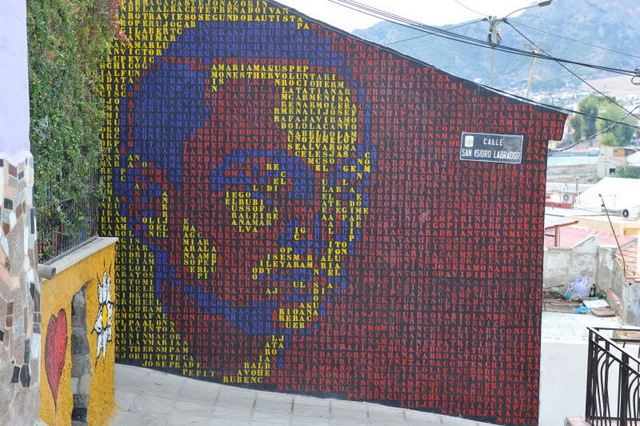

• The murals in the outlying district of San Isidro. These were created originally in 1976 in the San Isidro district on the outskirts of the city and are a tribute to Miguel Hernández, following Franco’s death in 1975. A process of restoration has been underway to recover the murals and they can be visited today, a powerful tribute to the poet and the ideals he stood for, in one of the poorest districts of the city.

NANAS DE LA CEBOLLA .

La cebolla es escarcha

cerrada y pobre.

Escarcha de tus días

y de mis noches.

Hambre y cebolla,

hielo negro y escarcha

grande y redonda.

.

En la cuna del hambre

mi niño estaba.

Con sangre de cebolla

se amamantaba.

Pero tu sangre,

escarchada de azúcar,

cebolla y hambre.

.

Una mujer morena

resuelta en luna

se derrama hilo a hilo

sobre la cuna.

Ríete, niño,

que te traigo la luna

cuando es preciso.

.

Alondra de mi casa,

ríete mucho.

Es tu risa en tus ojos

la luz del mundo.

Ríete tanto

que mi alma al oírte

bata el espacio.

.

Tu risa me hace libre,

me pone alas.

Soledades me quita,

cárcel me arranca.

Boca que vuela,

corazón que en tus labios

relampaguea.

.

Es tu risa la espada

más victoriosa,

vencedor de las flores

y las alondras

Rival del sol.

Porvenir de mis huesos

y de mi amor.

.

La carne aleteante,

súbito el párpado,

el vivir como nunca

coloreado.

¡Cuánto jilguero

se remonta, aletea,

desde tu cuerpo!

.

Desperté de ser niño:

nunca despiertes.

Triste llevo la boca:

ríete siempre.

Siempre en la cuna,

defendiendo la risa

pluma por pluma.

.

Ser de vuelo tan lato,

tan extendido,

que tu carne es el cielo

recién nacido.

¡Si yo pudiera

remontarme al origen

de tu carrera!

.

Al octavo mes ríes

con cinco azahares.

Con cinco diminutas

ferocidades.

Con cinco dientes

como cinco jazmines

adolescentes.

.

Frontera de los besos

serán mañana,

cuando en la dentadura

sientas un arma.

Sientas un fuego

correr dientes abajo

buscando el centro.

.

Vuela niño en la doble

luna del pecho:

él, triste de cebolla,

tú, satisfecho.

No te derrumbes.

No sepas lo que pasa ni

lo que ocurre.

Lullaby of the Onion

The onion is frostbitten

closed and poor:

frost of your days

and of my nights.

Hunger and onions,

black ice and frostbitten

great and round.

In hunger’s cradle

my little son lay.

With onion-blood

he was nurtured.

But your blood

Is frosted with sugar,

onions and hunger.

A dark-haired woman,

dissolved in moonlight,

spills herself ray by ray

over the cradle.

Laugh, little one,

drink the moonlight

if you must.

Lark of my house,

laugh on.

The laughter in your eyes

is the light of the world.

Laugh so that

hearing you, my soul

will fly through space.

Your laughter frees me,

gives me wings.

Banishes my solitude,

pulls me from my prison.

Mouth that soars,

heart that is lightning

on your lips.

Your laugher is a sword,

ever victorious.

Conqueror of flowers

and larks.

Rival of sunlight,

future of my bones

and my love.

The fluttering flesh,

Th blink of an eyelid,

Life as never before

painted.

How many goldfinches

soar and flutter

from your body!

I woke from childhood.

You never wake.

My mouth is sad.

Laugh forever.

Ever in your cradle,

defending laughter

feather by feather.

You’re a flight so high,

so extensive,

that your flesh is the sky

newborn.

If only I could

climb back to the source

of your launch!

For eight months you laugh

with five orange blossoms.

With five tiny

ferocities.

With five teeth

like five adolescent

jasmine buds.

They’ll be the frontier

of kisses tomorrow,

when you feel a weapon

between your teeth.

You feel a flame

running beneath your teeth

seeking the core.

Fly child on the double

moon of her breast.

It, saddened by onions.

You, satisfied.

Never give way.

Ignore what passes

ignore what happens.