Guidelines for submitting articles to Hacienda Riquelme Golf Resort Today

Hello, and thank you for choosing Hacienda Riquelme Golf Resort.Today to publicise your organisation’s info or event.

Hacienda Riquelme Golf Resort Today is a website set up by Murcia Today specifically for residents of the urbanisation in Southwest Murcia, providing news and information on what’s happening in the local area, which is the largest English-speaking expat area in the Region of Murcia.

When submitting text to be included on Hacienda Riquelme Golf Resort Today, please abide by the following guidelines so we can upload your article as swiftly as possible:

Send an email to editor@spaintodayonline.com or contact@murciatoday.com

Attach the information in a Word Document or Google Doc

Include all relevant points, including:

Who is the organisation running the event?

Where is it happening?

When?

How much does it cost?

Is it necessary to book beforehand, or can people just show up on the day?

…but try not to exceed 300 words

Also attach a photo to illustrate your article, no more than 100kb

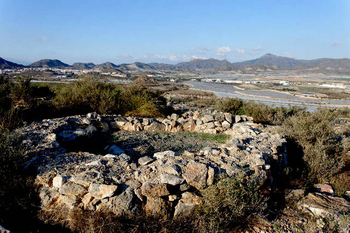

The Cabezo del Plomo in Las Moreras Mazarrón

Cabezo del Plomo, a 5,000-year-old Chalcolithic settlement in Mazarrón

Time scale 2980-3220 BC

This archaeological site is located on a long, flat-topped hill, looking out over the flood channel known as Rambla de Las Moreras or Rambla de Susana. It is strategically located in an easily defendable position with views of the sea, and although not linked to the Sierra de las Moreras, is protected by the mountains.

This archaeological site is located on a long, flat-topped hill, looking out over the flood channel known as Rambla de Las Moreras or Rambla de Susana. It is strategically located in an easily defendable position with views of the sea, and although not linked to the Sierra de las Moreras, is protected by the mountains.

This is one of the most important settlements discovered from what´s known as the Chalcolithic or Copper Age, and closely resembles one found in Los Millares in Almería, albeit on a much smaller scale, which was known to be inhabited at the same time.

Carbon dating on seashells found within this site has put firm dates for habitation at between 2980 and 3220BC, exactly the time Los Millares was inhabited.

This period in human development of man was a transitional stage, after the Stone Age, in which hunting implements and tools were made of stone and flint. People were developing skills in smelting metals, but had not yet developed the techniques of combining copper and tin to make the metal which would revolutionise human society - bronze.

This period in human development of man was a transitional stage, after the Stone Age, in which hunting implements and tools were made of stone and flint. People were developing skills in smelting metals, but had not yet developed the techniques of combining copper and tin to make the metal which would revolutionise human society - bronze.

Los Millares, which is 17km from Almería, was a vast fortified settlement, fortified walls enclosing a living area and houses, with a distinct burial area , an estimated 1000 people living within the settlement. Cabezo del Plomo follows the same principal, albeit on a much smaller scale.

This site represents the remains of what would have been a fortified village: on the higher part, the remains of the wall and the circular dwellings can still be seen and lower down the slope, just metres from the Bolnuevo road, are the remains of a beehive tomb, a round, almost igloo-shaped burial monument typical of the megalithic age remains found in this area.

Unfortunately, much of the burial element of this site was destroyed during quarrying for rock to build the new marina in Puerto de Mazarrón took place, so archaeologists are unable to estimate the population levels of this settlement.

Unfortunately, much of the burial element of this site was destroyed during quarrying for rock to build the new marina in Puerto de Mazarrón took place, so archaeologists are unable to estimate the population levels of this settlement.

The burial had also been visited by grave robbers, thieves having removed the stones which had fallen into the interior of the burial chamber, but it is possible to see the area of the tumulus and the chamber itself. The chamber was rectangular, and was built of large vertical blocks. Around it there were three niches.

This burial structure is similar to the older type of beehive graves or Rundgräber, and similar structures have been found on the hill of Canteras de Vélez Rubio, just over the boundary with Almería, and the dates tie in with habitation of this site by a culture in a similar stage of development.

When the burial structure was excavated, the remains of some burnt human bones were discovered, but in very small quantities, together with some shards of rough pottery, and "beads" from necklaces made from pierced shells, stones and bones.

When the burial structure was excavated, the remains of some burnt human bones were discovered, but in very small quantities, together with some shards of rough pottery, and "beads" from necklaces made from pierced shells, stones and bones.

Surprisingly for a site in which metal technology was undoubtedy used, no metallic remnants have been found, and there is no evidence of smelting.

Higher up the site is the residential part of the settlement. This is surrounded by a wall in the areas most vulnerable to attack, on the southern and western sides, while to the north and east, natural defences are provided by the steep slopes of the hill, which drop down sharply to the modern road.

The fortified wall is built directly onto the limestone rock, and consists of two irregular thicknesses of stones cemented together with mud. These two structures were built parallel to each other, the gaps of the inside one being filled with smaller stones to provide more solidity. Further reinforcement is provided by crude buttresses.

Inside the wall, four dwellings have been excavated to date, the dwellings being round, slightly oval-shaped structures, with a stone wall base, upon which a wattle and daub, reed and mud structure would have been built. The bases for the walls were made from two rows of irregular stones facing inwards, the gaps being filled with smaller stones, as in the defensive wall of the village.

Inside the wall, four dwellings have been excavated to date, the dwellings being round, slightly oval-shaped structures, with a stone wall base, upon which a wattle and daub, reed and mud structure would have been built. The bases for the walls were made from two rows of irregular stones facing inwards, the gaps being filled with smaller stones, as in the defensive wall of the village.

It has been estimated that the height of the dwellings would have been about 2 metres, each having a clean, tamped down earth floor inside.

The distribution of artefacts recovered from the site indicates that much of the daily work would have been carried out in the open. Few remnants of the daily tasks which would have been carried out by the inhabitants are found within the house structures.

On the surface ceramic remains from the Ibero-Roman period were found, (from 209 BC onwards) but this was of no surprise to the archaeologists excavating the site, due to the vast volume of Roman mines which litter the area. Beneath the Roman ceramic levels, flint arrowheads and even a flint workshop were found, although the flint found was of poor quality, together with a primitive stone hammer and grinding stones. Many shellfish were also in evidence: the gathering of shellfish from the coastline was clearly an important activity and source of food, and there were also bones of rabbits and boar, amongst other remains.

On the surface ceramic remains from the Ibero-Roman period were found, (from 209 BC onwards) but this was of no surprise to the archaeologists excavating the site, due to the vast volume of Roman mines which litter the area. Beneath the Roman ceramic levels, flint arrowheads and even a flint workshop were found, although the flint found was of poor quality, together with a primitive stone hammer and grinding stones. Many shellfish were also in evidence: the gathering of shellfish from the coastline was clearly an important activity and source of food, and there were also bones of rabbits and boar, amongst other remains.

Simple, rough ceramic pieces were also uncovered, but the quality was poor, and there was no evidence of any sort of decoration.

In the centre of the site, and covered by grids is a shaft leading down into a lead mine. The galleys from this stretch deep down inside the rocky outcrop.

Walkways have been prepared around the site and information boards prepared, although sadly these are now unreadable.

Accessing the Cabezo del Plomo site

Today the Cabezo del Plomo is accessed via the road between Bolnuevo and the roundabout with the steam roller on the centre island, and is next to the desalination plant.

Today the Cabezo del Plomo is accessed via the road between Bolnuevo and the roundabout with the steam roller on the centre island, and is next to the desalination plant.

At the foot of the hill is a small parking area, suitable for 3-4 cars. Access is via a steep, concrete-covered path. Flat, strong footwear is the only recommendation, and a walking stick would give a great deal of security, especially descending.

The Cabezo del Plomo archaeological site has been recognised by the regional authorities as part of Murcia's cultural heritage, although as with most of these valuable archaeological sites, it's been left a little untidy. There are several other interesting archaeological sites nearby, all with great views, and it a morning is sufficient to combine visits to them.

Within just a few minutes drive are the Punta de Gavilanes, Cabezo del Castellar and the salt falts of Mazarrón.

For more local information visit the home page of Mazarrón Today.

Sights to see in Mazarrón